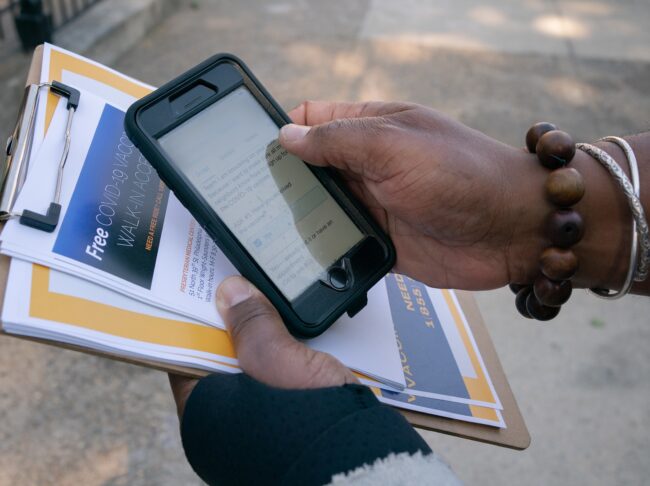

In May 2021, Yuhnis Syndor, 57, knocked on doors around West Philadelphia for several weeks, on a mission to save lives. He is a canvasser in the West Philadelphia Vaccine Street Team Pilot Program, part of a cohort that included graduate students, retirees, block captains and health care and hospitality workers. Each of them had personally been affected by COVID-19 in some way, were good listeners and believed in the value of the vaccine. And they shared a sense of purpose: “They want to dispel misinformation and show their neighbors [vaccination] is safe, by example,” said Natalie Ramos-Castillo, the canvassing field director.

The team formed as a joint community initiative between Penn Medicine, Third District City Councilmember Jamie Gauthier, and the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) Healthcare PA Training and Education Fund. The initiative grew out of a clear community need: Black West Philly residents were being vaccinated against COVID-19 at significantly lower rates than other racial groups in the city, consistent with the national trend of lower vaccination rates in Black communities. In a city where Black residents make up 42 percent of the population, only 21 percent of vaccines went to Black residents as of earlier in the spring, when the initiative was starting. As of late June, more than half of white city residents had received at least one dose of vaccine, but only about one third of African American residents.

Ramping up COVID-19 vaccination efforts through a professional canvassing model, similar to that used for political and issues-based campaigning, was an idea proposed by Tarik Khan, a nurse practitioner studying for his doctorate at the Penn School of Nursing, and nonprofit executive director Matt Goldfine—both of whom committed months of volunteer labor to get that idea up and running.

Canvasser Yuhnis Syndor, 57, speaks to Cristal LaTorre, 35, about the vaccine in West Philadelphia, PA, on May 20, 2021.

Initially, the canvassers aimed to get as many people as possible signed up for weekly vaccination clinics, before identifying a bigger issue: Vaccine hesitancy needed to be addressed, at a critical time. “Both regionally and nationally, supply started to exceed demand in terms of vaccine,” said Heather Klusaritz, MSW, PhD, director of Community Engagement for Penn’s Center for Public Health Initiatives.

“Our traditional ways of getting the word out about vaccines, whether through the news media, social media, or connecting with community and faith-based organizations, were no longer as effective.”

As more COVID-19 variants emerge, the urgency has only increased to help community members avoid serious illness or death. “It isn’t just about offering a vaccine clinic in the community,” Klusaritz said. “We are at a point where people need to build trust and create opportunities for people to have conversations about their vaccine concerns in order to support vaccine decision making.”

Stoop Sits Take on a New Meaning

Syndor and the canvassing team quickly changed their approach from clinic signups to focusing on connecting with neighbors and community members one-on-one in the 6th Ward. They extended the pilot to knock on more doors and share more information.

Over the course of 383 canvassing hours, canvassers visited 9,161 pre-mapped homes, answering questions about vaccinations while dispelling vaccine misinformation—all from the comfort of neighbors’ front porches. Most importantly, they listened.

More than half of those who engaged in conversations with the canvassers shared that they were already vaccinated.

Relatively few neighbors made the decision to get vaccinated over the course of their conversation, but when they did, it was a powerful moment.

Canvasser Yuhnis Syndor, 57, speaks to Alvin Banks, 57, about the vaccine in West Philadelphia, PA, on May 20, 2021.

“The most inspiring experience was when I was able to convince a mother who was extremely hesitant to get the vaccine to finally decide to get it after we had an open dialogue,” Syndor said. “Her son wanted to get the shot but for various historical, political, economic and social reasons decided that she was completely against the vaccine. We found common ground and she decided we were all in this together… She and her son got their shots the next day. I saw them both on the street and they came up to thank me profusely.”

More than 250 people talked with canvassers about feeling hesitant. Their reasons varied, from uncertainty about vaccination safety and religious reasons to stories from families and friends, and government distrust.

West Philly resident Christine Taylor, 45, who had been hesitant, was open to learning more about the vaccine after talking with Syndor. “I’m going to do the research because I learned some insightful things.”

The Work Continues

In just a few weeks, the pilot proved that local canvassing works and will continue to be a powerful tool against COVID-19 and future public health crises. It also solved an unexpected problem: Canvassers gathered critical data on homebound residents and helped those who had wanted to be vaccinated but hadn’t been able to leave their homes to get vaccines.

Armed with information and openness, Syndor and other canvassers feel they have the ability to chip away at the big challenge of vaccine hesitancy. In the words of one hesitant neighbor Syndor met during canvassing, “He’s got his points. He’s definitely got his points.”

On the ground, the power of persuasion and the gift of talking may be two of the best tools for encouraging vaccination and reducing misinformation. “I feel a change in organizing and helping people,” Syndor said. “I feel like I’ve been able to make a difference, just listening and having a conversation while educating.”

Ramos-Castillo has her eyes on other long-term benefits: “I deem any effort to engage with neighbors authentically with empathy and compassion as successful. Hesitancy about the COVID-19 vaccine can be alleviated through conversations that validate an individual’s experience with the medical system or misconceptions about vaccines,” she said. “The majority of those who were hesitant wanted to wait.”

Canvasser Yuhnis Syndor, 57, walks while canvassing in West Philadelphia, PA, on May 20, 2021.

Long-term canvassing success will require investment, continued efforts, and more touchpoints with neighbors, Klusaritz said. “For those who do have deep seated hesitancy concerns, for the most part they are not one-time conversations. A canvasser knocks on your door—it’s someone from your neighborhood who has had the same lived experience as you and is talking to you about vaccines, telling you some things that might help you change your mind, but you’re not ready yet. You still have some concerns and issues. Future efforts need to create additional opportunities for conversations with those who have concerns, who aren’t ready to make a decision, and provide information and support until they are ready.”