Often, when Bilikisu Abdulazeez would come for prenatal appointments this past spring and summer at the Helen O. Dickens Center for Women’s Health at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania (HUP), she’d also make a stop at HUP Harvest, the hospital’s food relief program a short distance down the hall.

There, she’d pick out a selection of fresh greens of her choice, along with pantry staples like rice, cereal, and organic tomato paste with which she’d make her kids’ favorite Nigerian dish, Jollof rice.

Abdulazeez’s husband, a scientist, supports their family. But with four sons—ages 11, 9, 6, and 3—Abdulazeez said the free, healthy food was a relief on a tight budget and a tight schedule.

“It’s easy because every time I go to an appointment, I don’t have to stop at a store to get anything to make lunch for myself and my kids,” Abdulazeez said in September, a few weeks before giving birth to her fifth son. “The boys eat a lot … It’s a way for me to help since I’m not working. I go to the food bank and I’m able to save some money.”

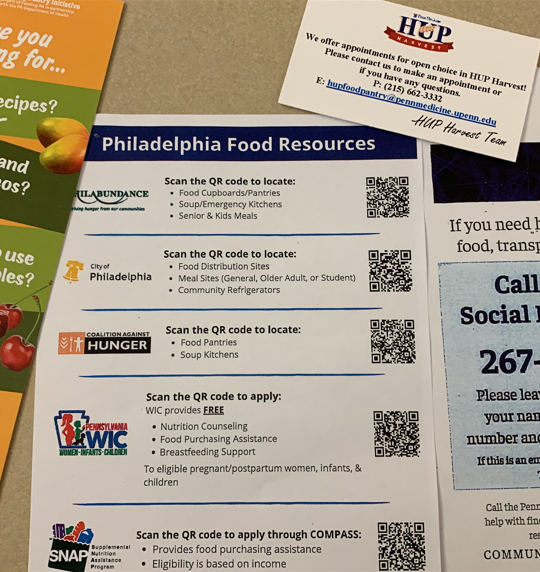

Philabundance, the city’s largest food relief organization, supplies both HUP Harvest locations with a minimum of 500 pounds of dry and frozen food each week at no cost. Becoming one of Philabundance’s member organizations in 2022 was a key milestone; having a reliable delivery of ample food made it possible for the program to expand to patients. In addition to the food from Philabundance, hundreds of pounds of fresh produce arrive each week from Penn Farm and Sharing Excess, a nonprofit that redistributes leftover food from grocery stores and restaurants.

The Penn Farm is located at the southernmost tip of Penn Park, and within clear view of HUP’s Pavilion. HUP patients and staff in need can pick up produce grown at Penn Farm via the HUP Harvest program.

Two Simple Questions

Nursing students supporting HUP Harvest ask two simple questions about food access for all expectant parents who receive care in the Dickens Center prenatal clinic and inpatients on the hospital’s postpartum and medical-surgical units. Patients can either answer verbally or in writing:

Within the past 12 months:

Were you ever worried that the food you had would run out before you could get money to buy more?

Was there ever a time when the food you had did run out and you didn’t have money to get more?

Patients who screen “positive” are either offered a bag of food to take home, customized for any dietary restrictions, or given a referral to “shop” at the pantry. Nursing students prepare medically tailored bags (a patient with heart disease, for example, won’t receive high-sodium items), or help patients with shopping appointments, making suggestions based on their diet.

Food insecurity is also covered on other inpatient units as part of a 13-question universal screening tool that went into effect this fall, covering a range of social, environmental, and economic factors that can influence a patient’s health, including housing, transportation, and utilities. Patients whose answers indicate they need help are then connected with the hospital’s social work team to line up possible solutions.

On the postpartum unit one day earlier this year, a patient named Julene happily accepted soup and other staples to take home for herself and her children following the birth of her third child. A self-described “workaholic” who had to stop working during a rough pregnancy, the former nanny said she wouldn’t have gone to a pantry on her own.

“When you’re been independent all your life, and have to ask for stuff, it’s hard,” she said. “This pregnancy was a rough one and work was up and down. I don’t have a job, and with bills and kids, you’re trying to live on the bare minimum at times.”

‘Whole Person’ Care without Stigma

The program’s name, HUP Harvest, was adopted in 2022 in lieu of “food pantry,” in an effort to both remove any shame or stigma associated with accepting food assistance and reflect the program’s expansive vision to offer fresh produce, recipes to cook simple meals at home, and other resources.

Beyond providing food, HUP Harvest has an important role in training the next generation of nurses and health care workers to see the full picture of patients’ lives, including their social needs, and not just the condition that brought them to the hospital, Carreno said. Students from Penn, Drexel, and other universities around the region have been critical to keeping the pantry organized, developing educational materials for patients and staff, and screening patients.

“It felt a little bit awkward going into patients’ rooms and knowing how to start a conversation about food insecurity,” one Penn Nursing student wrote in a survey. “Once we said that we were asking all patients these questions, it put the patients more at ease. Overall, patients and families were receptive and kind. I’m looking forward to becoming more comfortable initiating these conversations.”

Working with HUP Harvest helps students take a holistic approach to patient care by learning what other factors, outside the hospital setting, can impact a person’s health, said Drexel nursing instructor Monica Sidebotham, MSN, RN, who supervised a cohort of nursing students doing a 10-week community health rotation last summer with the program. “When we send a patient home, we want to set them up for success and help them address the social issues that could impact their overall health and well-being,” she said. “HUP Harvest is a great program for nursing students, as well as for the hospital staff and patients.”