Cherlynne Graham-Seay has lost track of how many times she’s told the story of the worst day of her life.

She can do it without flinching. She carries the story with her, wherever she goes, like a photo in her wallet. She can take it out and show you: See, this is what I survived. This is how I became who I am, why I’m doing the work I’m doing.

When she counsels her clients as a Penn Medicine community health worker; when she leads prayer vigils for nonviolence in the streets of Philadelphia; when she organizes gun safety classes for children through the nonprofit organization she founded — it’s all part of that same story, still unfolding.

Prologue

Raised in West Philadelphia, Graham-Seay was an intelligent young woman full of ambition when she landed a job as a secretary at the University of Pennsylvania in 1985. She didn’t have a college degree, but she was excited to find another way to be part of a university environment. “I knew that by coming to Penn I’d have more opportunities as far as growth and education,” she says.

And she was right. She went from secretary to assistant to office manager, eventually landing for 12 years as the department administrator for Classical Studies and Ancient History. There she set up colloquia, coordinated graduation lunches, and mingled with a slew of brilliant minds — from Michael Eric Dyson to Jesse Jackson to the young John Legend, in his days as an undergrad.

“I kind of grew up at University of Penn,” she says. “Basically I spent a quarter of my life there.”

She married a talented contractor and caterer named Joel Seay, and they had two boys: the firstborn they named Joel, after his father; the second son, they called Jarell.

The young family lived in West Philly, and they loved the neighborhood. Their house was always full of children; they hosted barbecues, block parties, Bible studies and book clubs. Life was good.

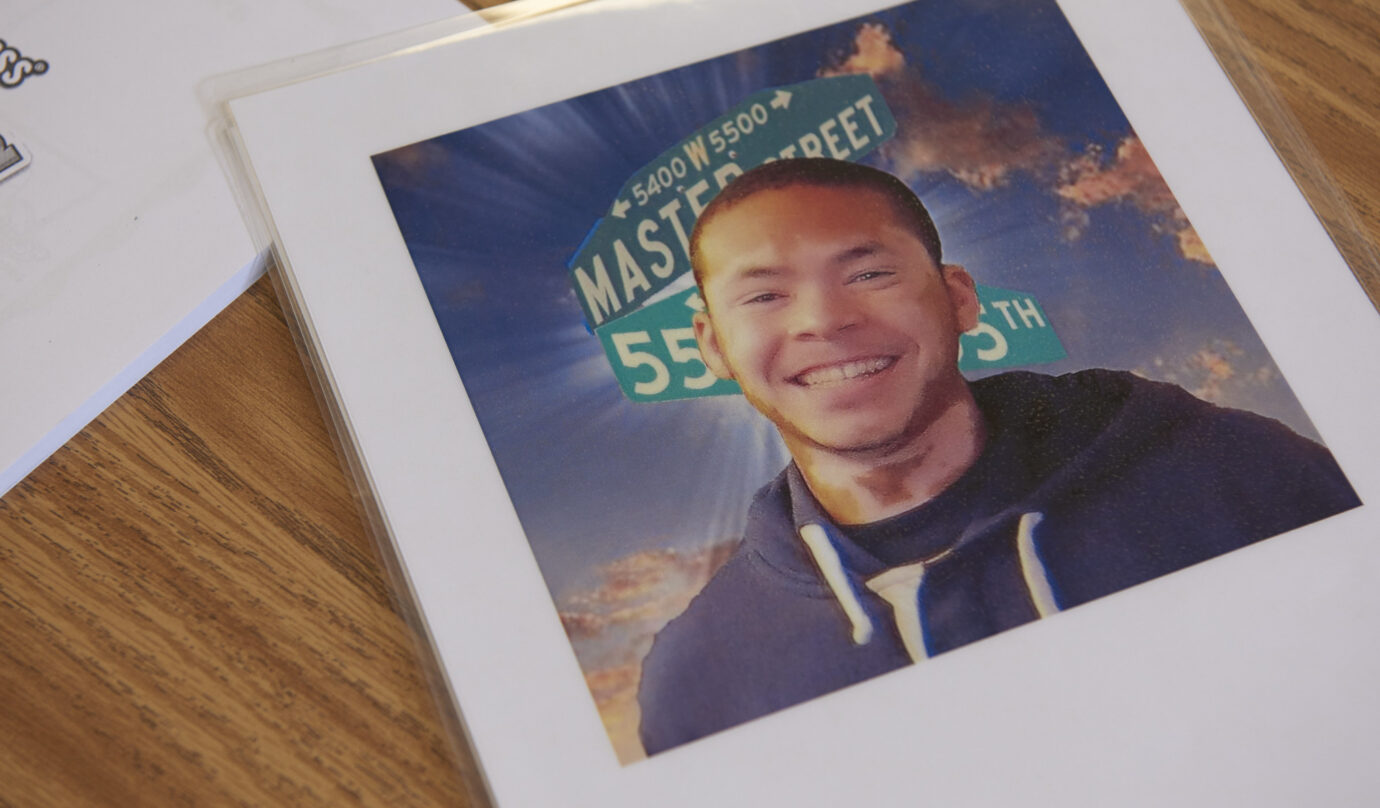

There were some challenges along the way. Jarell, a sunny, open-hearted child, struggled in school. Part of it was his vitiligo — an autoimmune condition that depigments parts of his skin on his face and hands, and for which he was bullied. He also had an unusual learning style, and he was held back in fourth grade. His parents eventually filed a suit against the school district for not meeting his educational needs. The settlement they won helped them send Jarell to a small private school where he excelled. As he grew, he became his father’s assistant in the construction business and helped his mother with the catering service she ran on the side. He was so positive that they nicknamed him Relish.

Then, after Graham-Seay’s 26 ½ years working for Penn, she was told her position was being terminated. Graham-Seay was crushed — working at Penn had been her whole career — but her husband reassured her.

“It’s okay,” Joel told her. “You’ll find something else.”

He was right — she was rehired six months later at Penn’s medical school.

With Jarell about to graduate high school and Graham-Seay settling into a new, stimulating job, it seemed like life was back on track.

On Easter Sunday in 2011, the family was finishing dinner when the doorbell rang, and Joel went to answer it.

It was a group of young guys, asking for Jarell. That was nothing unusual. Jarell was popular, and friends were often stopping by to see him. But something seemed off to Joel. “He said these guys just didn’t look right,” Graham-Seay recalled.

Jarell came to the door, and he stepped outside to talk to them.

Graham-Seay didn’t see what happened next. She only heard the screams.

Jarell had been shot.

Chapter and Verse

“It was the most horrific thing anybody could ever, ever go through.”

That’s what she says, every time she tells the story: “The most horrific day of our lives.” But it’s an understatement. There aren’t words adequate to communicate what it feels like to have the world blown out from under you.

The Philadelphia Inquirer described Jarell as “the mistaken target of a dispute between two rival corner gangs,” neither of which he was involved with. The police told the family he’d been a “soft target,” a surrogate victim.

It was an episode in an ongoing crisis — gun violence — that shows no sign of abating. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Jarell’s death was only one of nearly 470,000 gun-related fatalities between 2000 and 2014 — which would amount to an average of more than 30,000 deaths annually if it were a grim steady state. But it wasn’t. The situation has only worsened since then: In 2019, the CDC reported that gun deaths in the U.S. had reached a record high of 40,000 in the previous year.

A CNN analysis found that roughly 14,000 of those gun deaths were homicides — and of that number, half were young Black men like Jarell.

Now, Graham-Seay’s family was in free fall.

Joel Seay couldn’t stop reliving that day. He’d been standing next to Jarell when he was shot. In the aftermath, he was in agony and couldn’t bear to go to work, where his youngest son was no longer there to help him.

Graham-Seay coped by keeping busy: She went to back to work just three weeks after Jarell’s death. Sitting at home distressed her. “I wanted to keep my mind occupied,” she said. When she walked into the office, the supervisor said something to her she thought was odd: “The first thing out of her mouth was, ‘I’m surprised you came back.’”

There were other reactions to the murder that weren’t what she was expecting. In the neighborhood where the family had lived for 30 years, where they had always helped and supported their neighbors, doors closed to them.

“They seemed like they all turned their backs,” she said. “Nobody was saying anything, nobody would talk about who these guys were [who shot Jarell], they wouldn’t say anything to anybody.” Graham-Seay felt that her community had abandoned her.

She and Joel made arrangements to move. They signed the papers to purchase a home in another neighborhood. Shortly afterwards, at work, she was called to meet with HR.

Restructuring. For the second time, she lost her job at Penn.

For the next three years, she would search fruitlessly for a new job, draining her retirement fund to keep her and Joel afloat. It felt like they were in limbo: cut off from the home they’d known, cut off from work.

Around that time, she remembers that her father asked her if she was going to be okay.

“I got my faith and trust in God,” she said. “He’ll carry me through.”

She and Joel threw themselves into activism. By the summer after Jarell’s death, they’d founded a nonprofit organization in his name. Through the Jarell Christopher Seay Love and Laughter Foundation, “We intend to do something to wake people up to stop the killing,” Joel Seay told the Philadelphia Inquirer at the time.

They went to anti-violence rallies, led peace marches and vigils, and spoke on violence-prevention panels. They told the story of Jarell’s death so often it started to drain them, so they shifted focus: Through the foundation, they organized fundraisers, dance marathons, empowerment programs for young people, and gun-safety trainings. Charity activities they’d done for years — such as a back-to-school backpack giveaway for school kids, and holiday toy and coat drives — they did now in Jarell’s memory.

It helped to know that his life could mean something even to people who’d never met him.

But Graham-Seay knew they needed to do more — not for the community, but for themselves. She and Joel were dealing with the very real physical and emotional effects of trauma.

“For so long I couldn’t concentrate or think,” she said. “I couldn’t read a book. A lot of things I used to do, I couldn’t do anymore.” She heard Joel relive the experience with fresh pain in his sleep, saying, “You shot my son.”

She went looking for a therapist. She found Dr. Dorothy Mandelbaum.

“What is this older white lady going to do with me?” she wondered. “How is she going to help me?” But she quickly changed her mind. When her health insurance ran out, Mandelbaum said she’d see her and Joel for free — as long as they needed her.

“She was a blessing,” Graham-Seay says.

It took time — it took five years — but slowly they began to feel as if they could function again.

Turning New Pages

In the end, when Graham-Seay found her calling, it was through another mother who’d lost a son to violence.

She’d met the mother through the pastor of her church, and the mother had a friend who was a community health worker. “You and Joel are always helping people with your foundation,” she told Graham-Seay. “I have a job that would be great for you.”

That’s how Graham-Seay ended up coming back to Penn in 2016 — this time, not as an academic office administrator, but as a community health worker at Penn Medicine at Home.

This was a totally different kind of professional path, but it felt right. Instead of coordinating travel plans for university professors, Graham-Seay was helping Penn Medicine patients work to meet the health goals they had set with their doctors.

It’s all part of Penn’s Center for Community Health Workers, the home of the Individualized Management for Patient-Centered Targets (IMPaCT), a research-proven program that improves health through community health workers — trustworthy laypeople from local communities. The center was created about ten years ago by Shreya Kangovi MD, MS, an internal medicine physician and researcher from Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine, now its executive director. The program trains non-medical-professionals like Graham-Seay to work long-term with clients within primary care and after they’re discharged from the hospital.

Kangovi was able to show through three randomized controlled trials that the program not only benefits patients with chronic diseases and mental health, but also saves money by reducing hospital time and preventing people from becoming re-hospitalized.

Graham-Seay began working with clients for six months at a time, helping them improve their health day to day. Sometimes that means finding an affordable source for the medical equipment they need at home, or working with them to quit smoking and start healthier habits. Other times the work might seem to have nothing to do with health — at least not on the surface. Instead, Graham-Seay helps her clients counter the parts of their lives that had made them vulnerable to illness in the first place.

From her own experience with the mental and physical effects of trauma, unemployment, and grief, Graham-Seay is well aware that health can be a complex picture.

“It may be that a person can’t reach their health goal because they have all these other social determinants in the way,” she said. “They might need a place to stay. A child might need after care. There are so many different things.”

Sometimes, her role is as simple as providing a counterweight to loneliness. Once, she invited a client out to see a movie. It was the first time the client had left her house in a long time.

“It just goes to show you, you never know what’s going on in somebody’s world, what they’re dealing with, where they come from and what they’ve been through,” Graham-Seay said.

Her work can be frustrating, too — not because of the clients, but because of how much they’re up against. She talks about “broken systems”: health-care benefits that vanish if the recipient gets a pay raise, welfare payments that barely cover rent. These are the same broken systems that she sees in her work against gun violence. “Prevention receives little funding, while the prison and justice systems get all the funding needed to house criminals and do not provide effective training and rehabilitation to reintroduce them to society,” she wrote in an essay for Penn Medicine magazine.

“The systems put into place hundreds of years ago are not relevant to society today because they treat justice, education, mental health, and other systems as separate problems,” she wrote.

These are bigger problems than Graham-Seay could ever solve, but she’s doing what she can. She recently got her associate’s degree, and is pursuing a bachelor’s in human services. This winter, she was promoted within the Penn Center for Community Health Workers to become a program manager.

Through her nonprofit, she leads a Saturday group for local youth called Jarell Seay’s Defenders and an annual Jarell Seay Day of Play at Smith Playground and Play House in Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park. She also runs a program called Ladies In Power for Peace, or LIPP, where girls 12 and up learn about Black history, hygiene, beauty and health topics. Over the years, Graham-Seay and other Penn Medicine colleagues have supported the program by applying for Penn Medicine CAREs grants, and the Foundation has also received funding for its antiviolence efforts from the Philadelphia District Attorney’s office, other grants, and through its own regular fundraisers.

The goal is to support and inspire smart, empowered young people who know they have options for their futures that don’t involve standing on either end of a gun.

“The Seay Foundation’s programs encourage our youth to make smart choices in everything that they do,” Graham-Seay says. “They are taught what to do when danger presents itself and ways to avoid it by paying attention. We empower them by teaching our history and how African Americans helped to build our country and their contributions to society, and we also help them to understand that their current situation does not determine their life destiny.”

At its core, she says, the Foundation wants youth to break the cycle of violence and embrace its motto in all they do: “Let LOVE be the Power that Rules You!”

In December 2021, she spoke and joined a panel at a community symposium on Philadelphia’s gun violence crisis hosted by Penn Medicine. Local elected officials, community organization leaders, and Penn Medicine clinicians and researchers came together to find common ground and more thoughtful collaboration to address an escalating crisis: By the end of that year, the city saw a record 652 lives lost to homicide, most of them due to gunshots — as many as 652 families that just last year had the most horrific, painful day of their lives.

Graham-Seay told her story again that day in December. No matter how hard it is, she keeps telling it, over and over. Every time, it gets a little more hopeful.

After all, it isn’t finished yet.