“I’m not a real addict.”

Lancaster County, Pa. resident Kate kept telling herself this while in rehab for an opioid use disorder (OUD) that had started with medication she’d taken to manage pain. Three months on Percocet for arthritis left her with a dependency that would take the then-21-year-old to the streets when the prescription ran dry.

“I was justifying all of it because they were prescribed,” she said. “I didn’t want to deal with anything.”

After leaving rehab, she relapsed months later and had to move in with family. Then the pills became too expensive, so she briefly went to heroin. That’s when relatives stepped in, and she made the decision to check back into the same inpatient rehabilitation facility.

The real work began this time, she said, because she didn’t let her past — an unexpected death, abuse, witnessing drug use — hide any longer. She faced it in therapy and came out on the other side feeling healed. Today, Kate is 29 and sober, with repaired relationships and two children added to her family since she has been in recovery. Along with continued counseling to keep her healthy, she also takes lofexidine, a prescribed, non-opioid treatment that reduces her risk of relapsing.

“I’m not who I was, number one,” she said. “Number two, it’s almost like people are starting to understand it better…There is more help out there, and there’s less stigma.”

From the time Kate started battling her disorder to now, Lancaster County’s efforts to combat substance use have changed considerably. It began in 2017 when, faced with grim statistics, the county recognized it wasn’t doing enough. A total of 167 people had died of an opioid overdose that year, almost 45 percent more than 2016. The large increase in manufactured opioids and prescriptions had caught up with America, and OUDs turned into a full-blown epidemic in nearly every area, including Lancaster.

“The time for action is now,” Alice Yoder, executive director of Community Health at Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health (LG Health), told county commissioners in 2017. The county needed leadership and to coordinate its efforts, she said, to make the most of its resources and save lives.

A Community-Wide Push to Improve Treatment and Save Lives

Lofexidine, the drug Kate has been on for a few years, is what’s called a medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for opioid use disorder, and she receives it through one of the LG Health primary care physicians at an outpatient clinic near her home. It’s a safe and more private space to continue her care, she said. “When I go and talk to them, I don’t feel labeled. I don’t feel bad about myself.”

There has been a clear evidence base for years showing the effectiveness of plans like Kate’s that involve MATs and connect patients to professionals in mental health and social work.

Before 2017, however, a fully realized coordinated care program wasn’t in place in many hospitals — and given that a third of patients with substance use disorders first encounter the health care system in the emergency department, that was a missed opportunity for recovery. Patients would often be discharged without any clear path forward. What’s more, at that time, too few providers in EDs and outpatient clinics could prescribe MATs.

Tara M. Tawil, MD, a hospitalist and lead physician on the LG Health Drug and Alcohol Task Force, led the way on changing that at LG Health. Even before 2017, she had set out to educate herself and staff around her on substance use issues and the importance of intervention. She watched too many people leave her care and go back into dire situations.

LG Health’s efforts to improve access to treatments are interconnected with both the broader efforts at Penn Medicine under the institution’s opioid task force, and locally in the community, as part of a broad coalition called Lancaster County Joining Forces. Tawil is a member of both.

She was one of the first physicians at LG Health to become waivered for MAT, meaning she took an eight-hour course on treatments for OUDs that allowed her to prescribe the drugs. Taking MATs, research shows, significantly reduces the risk of a relapse. More physicians in the hospital and outpatient clinics followed, and today, there are over 215 LG Health providers who can prescribe MATs. Before 2017, there were only four. Across other Penn Medicine entities, more than 200 additional physicians and advanced practice providers can prescribe MATs — more in the city of Philadelphia than any other health system.

The local fight in the Lancaster County community began in earnest several years ago when LG Health and a group of other health systems, non-profit organizations, businesses, and government agencies came together to develop a cohesive and aggressive strategy to help more people like Kate through education and expanded resources. While the approach for Joining Forces remains multi-faceted and flexible, its charge has been singular and steadfast: reduce the number of deaths related to heroin and other opioids.

A Pennsylvania Centers of Excellence Opioid Use Disorder grant awarded to LG Health in 2017 helped build up the partnerships between the hospital and practices, and increase the number of MAT providers and counselors in the community, where screening for at-risk patients is vital to early intervention. Since then, more than 500 patients have been treated under the LG Health Center of Excellence.

“Right from the get-go, our premise was that we were going to be able to do more together than we would individually,” said Yoder, a member of the Joining Force steering committee.

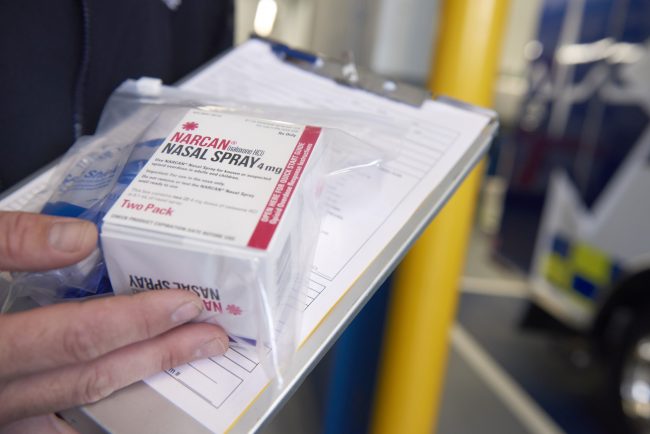

While increasing access to treatment is one of the coalition’s most recent successes, one of their immediate steps in the early days was to save lives as rapidly as they could by distributing Narcan — a life-saving medication that can reverse an overdose — into the hands of more emergency responders, police, school administrators, and community organizations. Grants from the Pennsylvania Commission on Crime and Delinquency (PCCD) and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) have assisted in making Narcan available, with over 5,400 Narcan kits distributed since 2017.

A “warm hand-off” program was also launched at LG Health and across other hospitals in the county, with the help of the Lancaster County Drug and Alcohol Commission, LG Health Centers of Excellence, and the RASE Project, a nonprofit that helps connects patients to care. It’s an integral part of this effort.

Through the programs, patients receive immediate help and recommendations for rehabilitation at all points of entry into Lancaster’s health systems. Similarly, Penn Medicine’s CORE, the Center for Opioid Recovery and Engagement, offers patients with substance use disorders at the downtown hospitals comprehensive support to ensure they receive continued treatment. The services are free, regardless of insurance. Chester County Hospital and Princeton Health also engage with patients through warm hand-off programs.

“[Joining Forces] and the Centers of Excellence helps us create the community connection when patients come to the hospital,” Tawil said. “When I start someone on medications for opioid use disorder, I can easily pick up the phone and say, ‘You are going to be meeting this patient after discharge and this is why they are coming to you. This is the journey they have had.’”

All of these approaches to improving treatment — as well as prevention, through efforts to reduce prescriptions of pain medications — have led to results for the outcomes-oriented local community coalition. By 2018, the number of deaths had dropped from 167 to 108 in Lancaster County. There were 104 deaths in 2019.

“I think because of the way our community has worked together on common issues and built trust among partners over many years, it has allowed us to respond quickly to the opioid crisis and make real long-lasting changes,” Yoder said.

New challenges to the efforts came along in 2020, however. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the requirements to reduce the number and density of in-person gatherings means recovery meetings have switched to a virtual setting.

For some individuals in recovery, it has been easy to transition to online support group meetings, but more challenging for people in under-resourced communities with limited access to computers and internet. That lack of social connectedness has led to more relapses and more overdoses. At the end of 2020, 146 drug-overdose related deaths were reported, which surpassed the previous two years.

Changing Lives Through Community Education

Kate’s earlier trauma and her medical condition led to her substance use. But it’s a disease that finds people from all different angles. Others suffer from anxiety or depression, and end up turning to drugs to cope. Some are younger. Some are older. Some are Black or Asian. Some are white or Latinx.

“Addiction doesn’t discriminate,” Kate said. “It doesn’t matter who you are.”

That’s why Lancaster County’s Coalition efforts are greatly augmented with education from health care providers and other key interveners improve their ability to prevent and treat OUD.

Joining Forces initiated an all-out media campaign in 2017 that included the distribution of informational materials to the public and health care providers. Within that first year, more than 100,000 packets went out to the community. Where to find resources, how to lock up medications, where to dispose of them, who to call — they covered a host of topics.

Billboards around the county, emblazoned with phrases like “Serious addiction can start with a simple prescription,” directed people to the Joining Forces website on where to get help. The foundation of our framework for action is a comprehensive approach that includes awareness, prevention, treatment and recovery.

“That was one of the most important things…working collaboratively with our partners to identify key messages, fact-based information that we can share with the community,” said Christine Glover, a health promotion specialist at LG Health. “Because across the board, not just in schools, there really was a lack of awareness about opioid safety, substance use disorders, and where to get help. So we really identified the ongoing need for consistent messaging that reflected all the science we know.”

That also meant going into more Lancaster schools. Working with the non-profit organization Compass Mark, Joining Forces replaced outdated scare tactics with science-based prevention that focuses on skill-building. A more recent effort, known as Joining Forces for Children, centers on higher-risk children whose households are experiencing addiction. A survey of EMS providers showed that a child was part of a household of nearly 83 percent of opioid-related overdoses.

“We’re trying to boost their protective factors to reduce the likelihood they develop substance use disorder or develop mental illness,” Glover said, “so that they can succeed in school and their overall health and well-being is improved.”

Dissolving stigma, one of the toughest factors that keep substance use disorders alive and well, is part of the equation here, too. Shame and ignorance prevent many people and families from facing the issue in a healthy and effective way, which can prolong recovery or, worse, prevent someone from receiving help before it’s too late. “Back in early 2017, many people didn’t think about addiction being a disease,” Yoder said. “They thought it was more of a character flaw.” But over the last three plus years, as Joining Forces made its presence known and impact, she watched the community’s perceptions change.

“People started to freely talk about someone that they love or in their families that are struggling with addiction,” Yoder said. “And if you are free to talk about it, then hopefully you have the freedom to get or ask for help. We need to be there for people.”

The fight continues. But it’s evolving. An uptick in the use of other drugs, like stimulants, has the coalition shifting resources, while still working to reduce deaths related to opioids and heroin. That’s a benefit of having a built-in infrastructure and community capacity — it positions Joining Forces to address other crises in the future.

To the people struggling today, Kate wants to send a message from her own experience that it’s not always easy to find and accept help or admit how deep the problem runs. But the important part is that a support system, now stronger than ever, is there waiting, even in a pandemic.

“You definitely don’t have to continue to live with addiction; you just have to actually want the help,” Kate said. “The first time I wasn’t ready for it. The second time I was. There is hope.”

How A Local Community Joined Forces to Save Lives

How A Local Community Joined Forces to Save Lives