At the Church of Christian Compassion on Cedar Street, volunteers from Penn Medicine, Mercy Philadelphia Hospital, and the church began arriving in the chilly dark of 6 a.m. February 13. Clad in black T-shirts printed with “Mercy & Penn Medicine & The Community #VaccineCollaborative,” they set up tables and chairs in the church’s lobby and classrooms, assembled supplies and paperwork, and hung dark coverings over the windows to lend privacy to those inside. Converting the church into a makeshift medical clinic, the volunteers were well-prepared for a long productive Saturday. By a bit after 3 p.m., 500 parishioners of West and Southwest Philadelphia church congregations had been vaccinated against COVID-19.

The event was the start of a series of pop-up neighborhood clinics co-organized by Penn Medicine, Mercy Catholic Medical Center-Mercy Philadelphia Campus, and city faith leaders, emerged from the understanding that people of color have been hardest hit by the pandemic and are also more likely to be uncertain about becoming vaccinated.

After the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines were authorized for emergency use in December, Brennan and Phil Okala, chief operating officer of UPHS, discussed how they could address the racial disparities at play in the pandemic and specifically those related to vaccine distribution. In Philadelphia, only 12 percent of the vaccine had gone to Black residents by late January 2021, even though this group makes up 42 percent of the city’s population.

“We figured one way to go about this was to engage the faith leaders, the pastors of West Philadelphia,” said Okala. “To engage them as influencers, helping assure their congregants that the vaccine is safe, seemed like a wonderful idea all around.”

Okala contacted the Rev. William Shaw, pastor of West Philadelphia’s White Rock Baptist Church and a member of the Penn Medicine Board, who invited more than 20 additional pastors to participate in a conversation about making a vaccine event a reality.

“The pastors were from across the spectrum,” Okala said. “Some were already convinced they would take the vaccine; others were not. But we all agreed it was a good idea to host a vaccine clinic in West Philadelphia, so people could come get the vaccine in a place they were comfortable.”

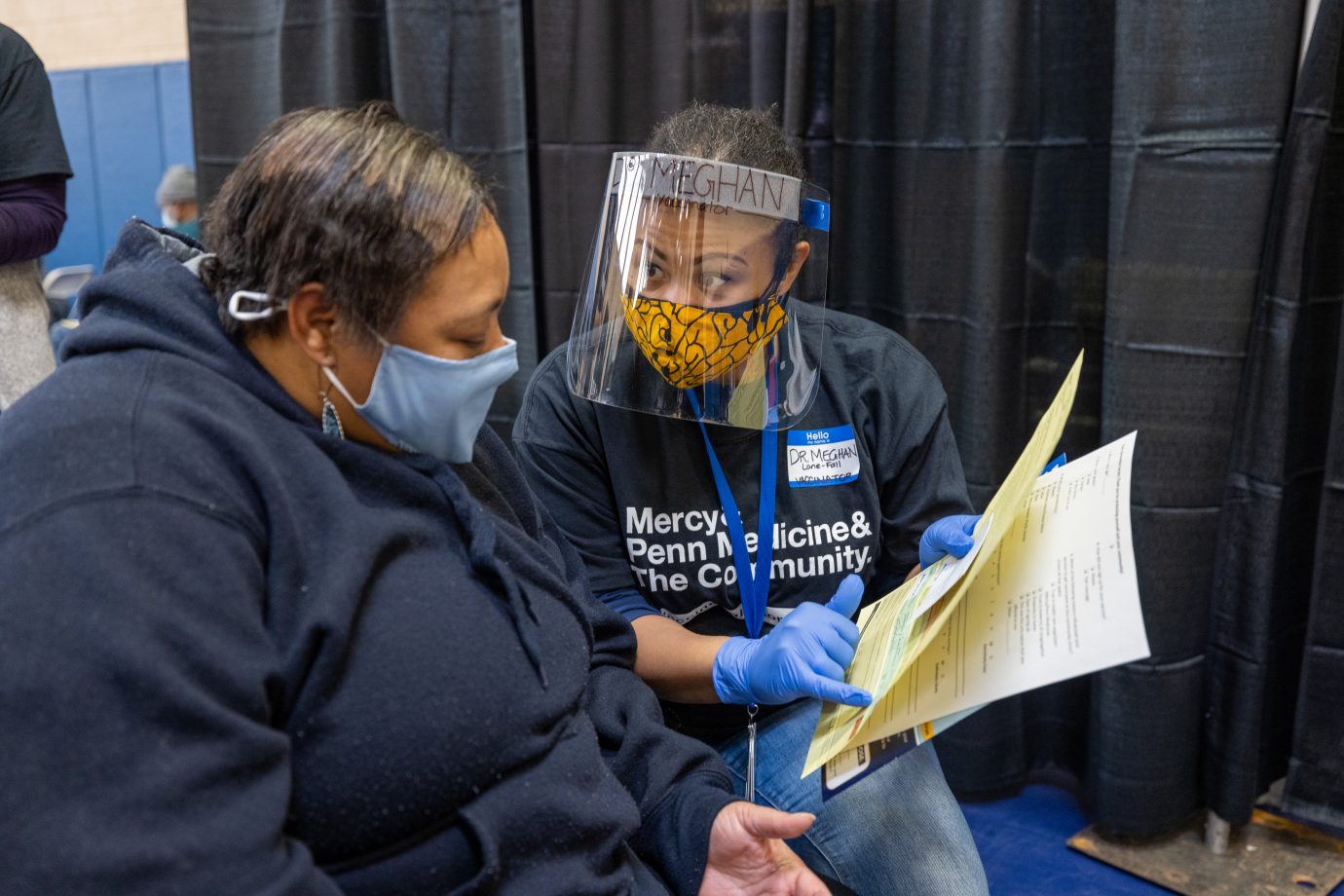

A volunteer reviews information with a patient awaiting their COVID vaccine at the Church of Christian Compassion. Appointment slots for the church’s vaccine clinic filled up within minutes.

“I think we are making progress, but progress is gradual,” Okala said. “We are not going to erase 400 years of ill in one go. We have to be steadfast.”

Meghan Lane-Fall, MD, MSHP, was among the volunteers at the School of the Future clinic. When sharing why she chose to get vaccinated, Lane-Fall said, “I’m a scientist who knows that this is our best chance to turn the corner on the pandemic,” adding, “Black people have too often been denied cutting-edge science.”

Signs of progress were evident in the upbeat atmosphere at the first February clinic.

“We have turned our church into a hospital today,” said Pastor W. L. Herndon of the Church of Christian Compassion on a Facebook Live broadcast during the clinic. “There are some people who wouldn’t go to a place other than a place that they trust,” he said, recounting a conversation he had with a 78-year-old woman who had gotten vaccinated who hadn’t hugged or touched her children in nearly a year due to the pandemic. “That’s why this matters.”

It was a sentiment echoed by a couple of just-vaccinated parishioners overheard leaving the clinic: “Today is a good day.”

Along with the clinic at the Church of Christian Compassion, additional clinics were held at the Francis Myers Recreation Center, School of the Future, and the Preparatory Charter School in South Philadelphia, vaccinating a total of nearly 4,000 people across the clinics.

A retrospective of the efforts on the three initial clinics was published April 7 in NEJM Catalyst. The team reported that 85 percent of the people vaccinated at these clinics were Black, helping to address the underrepresentation of Black Philadelphia residents in receiving the vaccine overall. Knowing that some residents struggled with various online portals for vaccine sign-ups and scheduling, adopting a low-tech/no-tech approach was one of the keys to their strategy to promote health equity. Based on consultation with community members, the Penn Medicine team devised two methods to reach out to potential patients to make sign-ups easier for them: one where text messages with easy sign-up processes were automatically sent out, and another phone-based system run by a dedicated team.

To sign up for a shot via text, all patients had to do was respond to a series of questions with “Y” or “N” and their zip code to confirm eligibility, and then the next few text-based questions collected their registration details and offered appointment times — as well as the option to repeat the process on behalf of friends of family members at the end. The approach was one of several key lessons learned that they hoped to share to help others extend their impact beyond Philadelphia’s local communities.

“Addressing the vast disparity in both COVID outcomes and vaccine distribution is a critical priority both locally and nationally,” said the paper’s lead author, Kathleen Lee, MD, director of Clinical Implementation in the Penn Medicine Center for Health Care Innovation and an assistant professor of Emergency Medicine. “We wanted to share our insights in the hope that this will both bring further attention to the issue and help inform the efforts of others.”

This story was written by Katherine Unger Baillie and an earlier version was originally published on Penn Today. The story has been updated to reflect additional clinics and data available as of the date of publication, April 14, 2021.

Engaging Faith Communities to Reduce Vaccination Disparities

Engaging Faith Communities to Reduce Vaccination Disparities