Stacy Hill knew that she was due for a colonoscopy. She’d been scheduled to get one years ago, but cancelled it when she lost her job and with it, her health insurance.

Then in October 2020, her church, the Enon Tabernacle Baptist Church, held a Flu-FIT drive-through event. Community members who were due for colorectal cancer screenings could both get their flu shot and pick up a fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) Kit, an at-home screening test for colorectal cancer, at the same time. “I was just there to support the church. I didn’t think anything of it,” said Hill, who has been a member there since 2004.

When her FIT kit came back positive, Penn Medicine, which sponsored the clinic along with Einstein Health, worked with Hill to schedule her for a colonoscopy in January. Then, she had abnormal polyps removed. She had another colonoscopy again two months later, which required more polyp removal. She will get another colonoscopy in October.

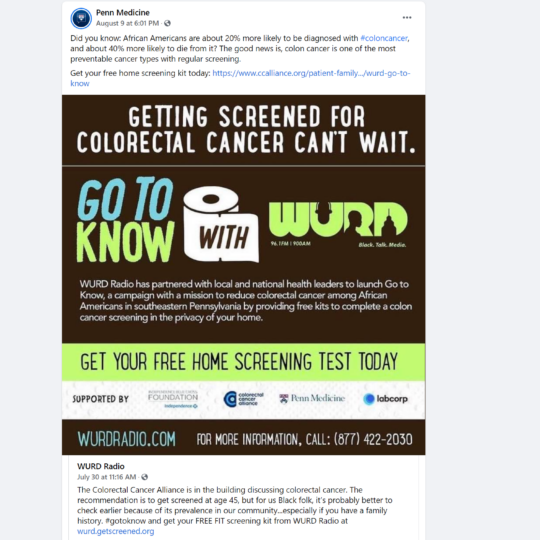

Penn Medicine has been on a multi-year journey to both raise the rates of screening for colorectal cancer and increase uptake of follow up care, with the goal of driving down colorectal cancer death rates and addressing inequities. Right now, colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death in the U.S., with higher rates in the Black community than any other racial/ethnic group. Black Americans are 20 percent more likely to get colorectal cancer, and 40 percent more likely to die of it compared to most other groups, according to the American Cancer Society.

“It’s not one thing that’s causing the disparity. It’s a series of small failures at every step. When you add those small failures together, you get a big disparity like this,” said Richard Wender, MD, chair of the department of Family Medicine and Community Health at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, and chair of the National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable.

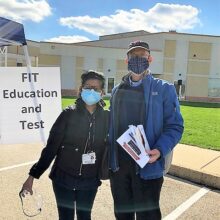

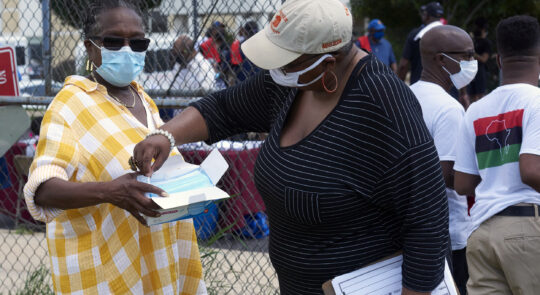

Preventive steps to address health disparities for Black men and women were on the agenda during the Bro Stroll held on Juneteenth, June 19, 2021.

More screening alone won’t fix the racial disparity, but it’s an important start. And Penn Medicine is taking that running start in multiple ways: not solely relying on patients scheduling colonoscopies, but partnering with community health centers, churches, and community groups to distribute at-home testing kits, and pulling data from electronic health records to mail kits to patients who need to be screened.

In this first step of increasing screenings, there are already signs of success.

In the last fiscal year, 70.41 percent of Penn’s Black adult patients age 50 to 75 were screened for colorectal cancer, up from a baseline of 69.7 percent almost a year earlier and similar to the screening rate for white non-Hispanic patients.

Not only is that higher than the overall 68.8 percent rate in the U.S. of all adults in 2018, the last year data is available, but Penn achieved this during the pandemic, when patients were less likely to come into healthcare settings, and when almost every other cancer screening rate fell.

“If we can help eliminate those barriers to accessing colorectal cancer screenings, we would find it earlier and maybe prevent its progression, and reduce the rates of colorectal cancer death in our region that disproportionately falls on Black and Latino patients,” said Armenta Washington, MS, senior research coordinator at Penn Medicine. “We can make a real difference in our communities, and save lives.”

Claudia Melendez, a Penn undergraduate volunteer, and Armenta Washington, senior research coordinator at Penn Medicine, gave out FIT testing kits to eligible participants at a Juneteenth event at Enon Tabernacle Church.

Simplifying Screening in the Community

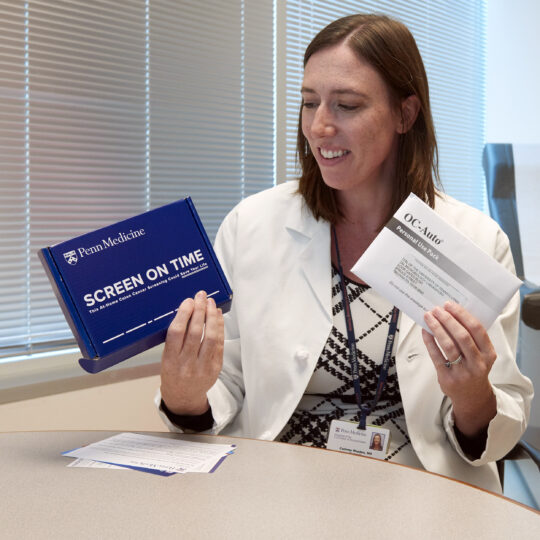

Colonoscopies are the most sensitive test for colorectal cancer “as they can detect both polyps and cancer,” said Shivan Mehta, MD, MBA, MSHP, associate chief innovation officer at Penn Medicine and an assistant professor of Gastroenterology and Medical Ethics and Health Policy. If an abnormal polyp is found during the procedure, it can be removed right then and there. “If patients receive a colonoscopy, they reduce their chances of dying from colorectal cancer by 50 percent,” he said. It also only needs to be done once every 10 years.

But the procedure itself is just that: a procedure. It’s invasive, unpleasant, and time consuming. “The patient has to take a day off work. They also have to have an escort who has to come with them because they’re getting sedation. They have to drink the prep the night before. It’s not a simple test,” he added.

A colonoscopy isn’t the only way to screen for colorectal cancer. At-home testing kits use a stool sample, collected by the patient at their convenience, to test for the presence of blood, which can be a signal that polyps or cancer is present in the colon or rectum. A FIT kit, which Penn Medicine uses for population-based screening in addition to colonoscopies, can be as effective in reducing the burden of colorectal cancer as colonoscopy if it’s done every year.

Penn Medicine has launched two efforts into getting FIT kits to people who are at high risk of colorectal cancer, both of which address every step in the colorectal screening process: identifying who could benefit from an at-home kit, following up to make sure they drop off or return kits, and then helping those who test positive get colonoscopies, in some cases helping them obtain funding and/or health insurance to cover the costs of treatment.

One such effort is the drive-through health fairs, including the one that helped Stacy Hill learn she needed further testing and treatment. Helmed by Carmen Guerra, MD, MSCE, FACP, an Internal Medicine physician and vice chair of diversity and inclusion for the department of Medicine, and Washington, these events partner with community groups and churches to hold drive- and walk-through screenings.

They were supposed to do their first event in March 2020 tied to the March Madness NCAA basketball tournament, but it was cancelled because of COVID restrictions. When actor Chadwick Boseman died of colorectal cancer on August 28, 2020, at age 43, it was a shock. His death prompted the team to figure out how they could pivot to still make screenings happen in an outdoor socially distant setting.

That led to the first drive-through FIT-Flu event, held in October 2020. Guerra and Washington partnered with Enon Tabernacle Baptist Church and Einstein Health’s Gastroenterology Chief Michael Goldberg, DO, to hold a drive-through event where participants could get both a flu shot and a FIT kit.

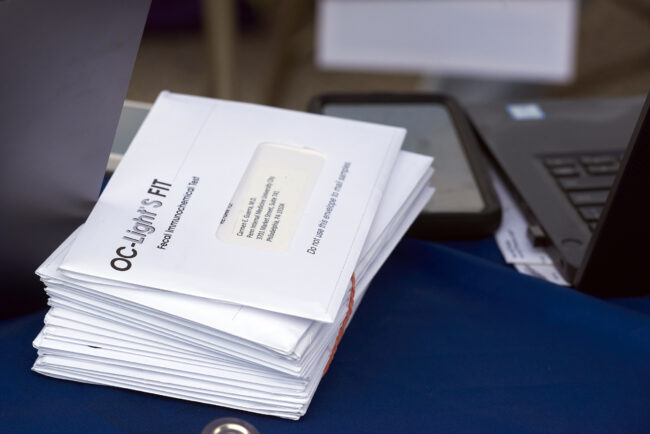

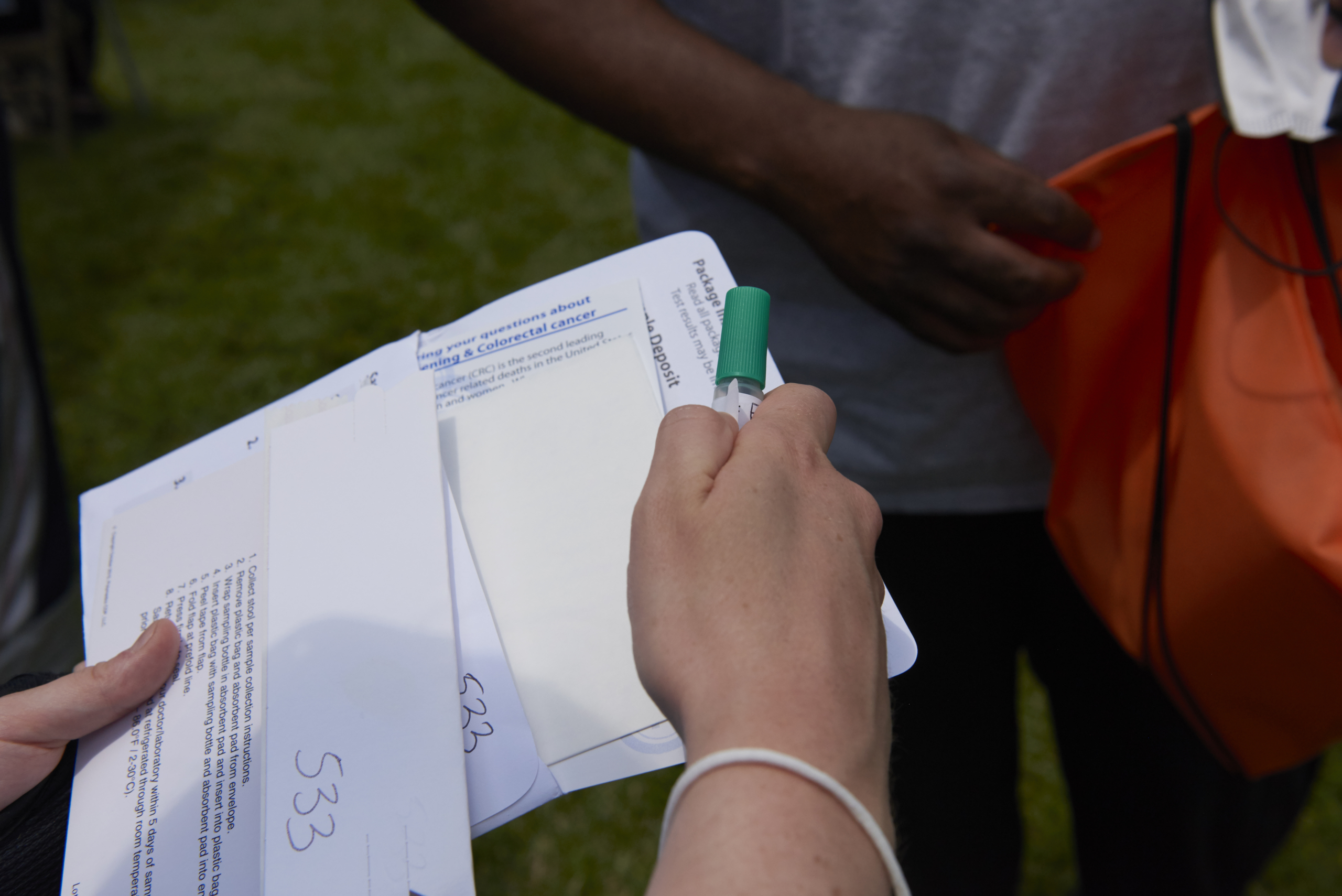

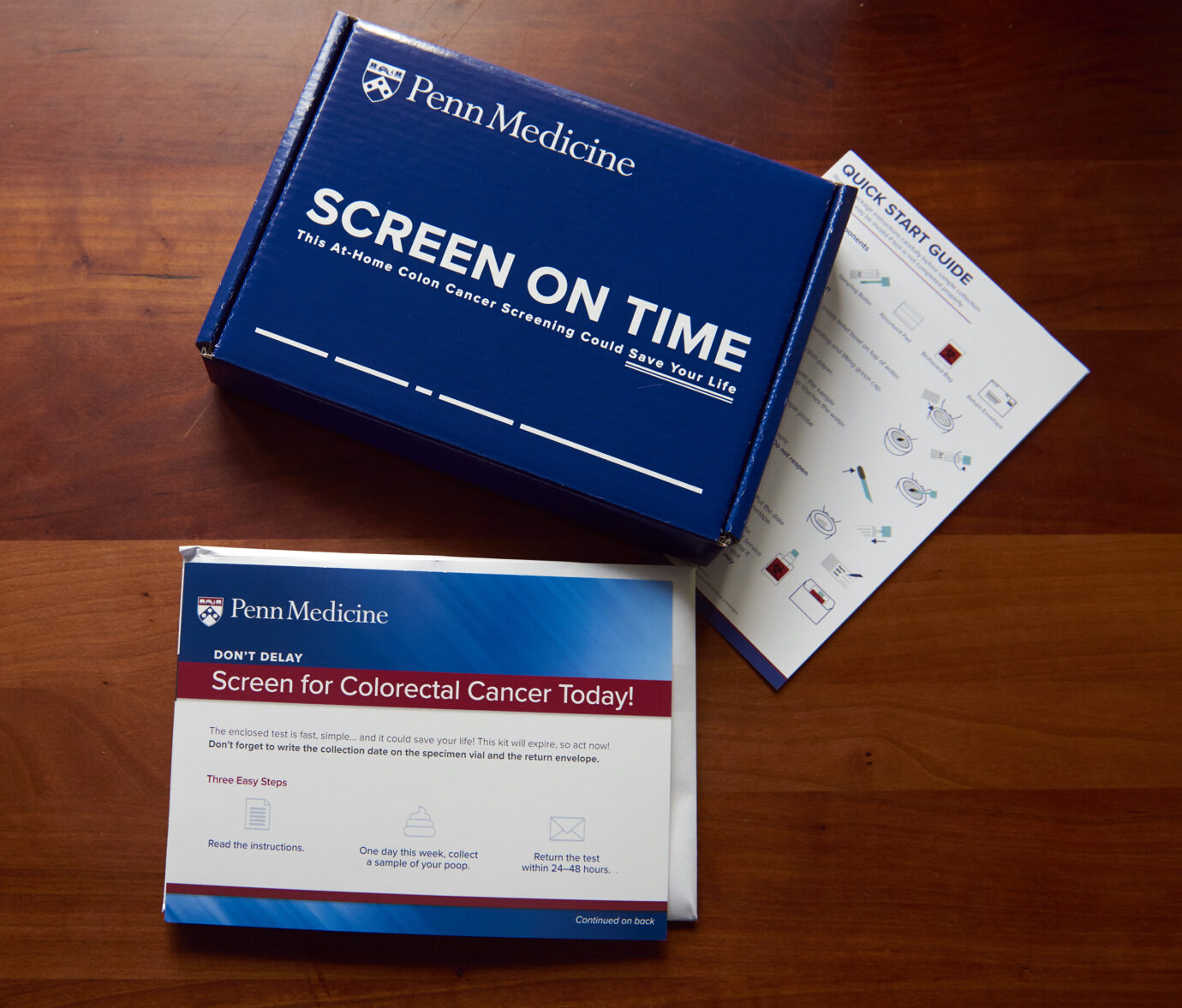

A FIT Kit comes in an envelope and includes instructions, a prepaid return mailing envelope, and a small tube to contain a probe that the user will insert into a stool sample to capture a tiny particle. In the lab, the small sample is tested for signs of blood in the stool, which may not be visible.

In another community outreach-based initiative, Guerra and Washington along with another Penn Medicine colleague, Akinbowale Oyalowo, MD, MSHP, also worked with the Colon Cancer Alliance (CCA) and Independence Blue Cross Blue Shield to pay for testing kits, and WURD, Philadelphia’s African American owned and operated talk radio station, to promote colorectal cancer screening especially among Black Philadelphians.

“With any kind of community-based intervention, you want to work with the people in the community and find trusted sources of communication, and WURD checked both those boxes,” said Oyalowo, an assistant professor of Gastroenterology at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

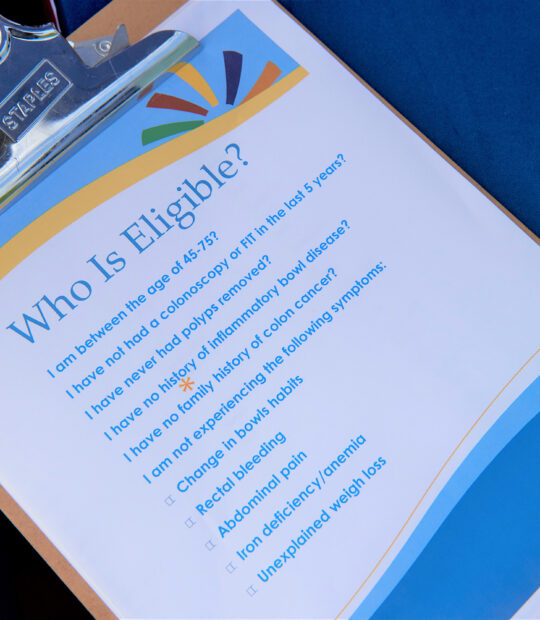

Through the WURD awareness campaign, community members signed up online and were connected with a CCA navigator to make sure they were appropriate for screening before a FIT test was mailed to them.

For the drive-through fairs, Enon congregants and community members were invited to pre-register through a Penn portal, through which Penn Medicine identified who was at high risk and late on getting a colon cancer screening. If someone qualified for a kit, they could drive through and, in one swoop, get both their flu shot and pick up a FIT kit without having to leave their car (participants who didn’t have cars could walk up). They could then return the kits to Enon Tabernacle Baptist Church.

The drive-through format was built on a formula that worked. The church had already had success with drive through food distribution programs during the pandemic, said Reverend Leroy Miles, associate pastor at the Enon Tabernacle Baptist Church, where they’d put groceries right in the trunks of cars.

“Some people picked up the kit that morning and brought it back that afternoon, and we would pause and clap for them,” Miles said. “Using the church as a drop-off point really helped the process and made it seamless.”

If someone took but didn’t return a kit from a drive-through fair, Washington and/or Tifane Voras, RN, a nurse navigator from Einstein Health, followed up and do what they could to get the completed kit back. Washington collected kits from patients’ homes, and even had her uncle, who lived in the neighborhood of a few patients, pick up the kits for her.

In both the drive-through fairs and the WURD/CCA campaign, if someone tested positive, then nurse navigators helped them schedule a colonoscopy. If they were uninsured, they would help them schedule an appointment at a free clinic, and in some cases help the patient sign up for health insurance.

“It just shows that you can reach out to patients directly and side step some of those barriers that might otherwise prevent people from getting this type of cancer screening,” Oyalowo said.

At five drive-through/walk-through events, the team registered 449 people. Of those, 251 collected FIT kits, and 202 kits were returned — at over 80 percent, a high rate for this kind of test.

In addition to the five drive-through/walk-through events at Enon Tabernacle, the Penn Medicine/Einstein team partnered with the church to give out additional FIT kits during the Bro Stroll on Juneteenth.

Of the returned kits, 187 were negative. The 15 patients with positive kits were referred to colonoscopies. Ten patients received them; seven patients, including Stacy Hill, had abnormal polyps removed.

Miles said this effort isn’t just about the number of kits collected and returned. “It’s about the conversation around colon cancer and getting folks screened, which seem to be increasing exponentially,” he said. “Just like blood pressure, just like glucose, we really want to make these non-invasive screenings available. It’s just too easy. It’s doable.”

Delivering the Message at Home

In addition to community-based screening, Penn Medicine is also reaching out to patients via mail. In June, they sent almost 4,000 kits to Penn Medicine primary care patients based in communities with low screening rates, who were themselves not up to date on their colon cancer screening according to their electronic health records.

The kits’ user-friendly boxes were designed to look more like a consumer product than a medical test to make them more appealing. Text messaging and behavioral economics were also integral to approach, building on Penn Medicine’s extensive experience with innovation and research using these tools to help patients stay healthy.

“Everyone uses text messaging, but a lot of health care providers haven’t realized the technology’s potential yet,” said Mehta, who has published studies in Preventive Medicine Reports, the American Journal of Gastroenterology and JAMA Network Open about using behavioral economics to increase screenings.

Mail gets lost or isn’t opened. Patient portals aren’t an ideal solution either, especially for patients who may not have reliable internet.

“It could exacerbate disparities. But 90 percent of our patients have some sort of cell phone with text messaging capabilities. It’s an equalizer,” he said.

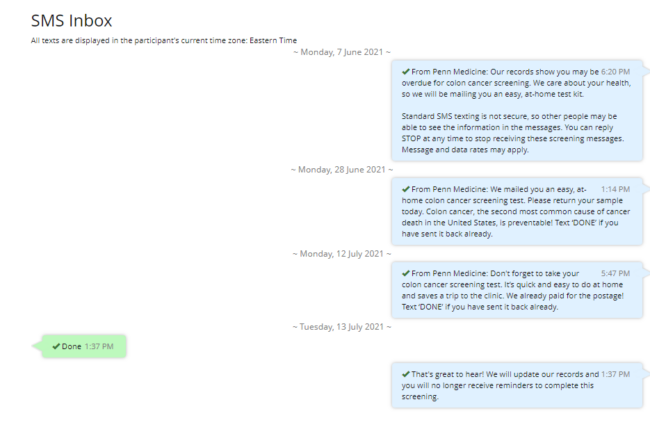

Patients who were selected for this at-home screening outreach received a basic text message from Penn Medicine: “According to our records, you are overdue for colon cancer screening. We care about your health, so we are mailing you an easy-at home kit,” along with standard language about how they can opt out of screening messages.

Instead of patients needing to opt in to getting a kit, they had to opt out, which makes them more likely to accept the kit, Mehta said.

Three weeks after Penn mailed the kits, patients got a follow-up text message: “We mailed you an easy, at-home colon cancer screening test. Please return the kit today. Colon cancer, the second most common cause of cancer death in the United States, is preventable! Text ‘DONE’ if you have sent it back already.”

Two weeks later, another follow-up message to those who hadn’t returned their kits included a reminder of how easy and convenient it was.

Of the 4,000 kits mailed in June, over 600 recipients initially responded. The team is tracking but not yet ready to release data on the progression of the kits and additional kits returned in the weeks since.

Getting access to at-home testing is just one step of many. The leaders of Penn Medicine’s screening initiatives recognize that this is still just an entry point into the effort to help more patients both catch and treat colorectal cancer early, and to do so equitably. Even after gaining access to screening, patients who face hurdles to accessing health care “will be less likely to have follow-up colonoscopy if the non-invasive test is abnormal,” Wender noted. “They’re less likely to finish their diagnostic work up, and less likely to initiate treatment in timely way or to initiate treatment at all if cancer is found.”

But the results are promising, and a sign that this program could move beyond just Penn Medicine primary care patients to improve access to screening and treatment more broadly. “We need to go to people who live in our communities, whether they are Penn patients or not,” Wender said.