The HIV testing sites where Meredith “Page” Miller has worked couldn’t be more different.

One is a truck that parks next to a rural health clinic three or four times a year in the Eastern Province of Zambia, Africa, where many residents of surrounding communities live without electricity or running water, and walk up to five hours to get health care. They cook over fires and fetch water from wells hundreds of feet away from their thatched mud huts, just like Miller did when she lived there as a community health advisor for the Peace Corps in the tiny farming village of Chaingo.

More than 7,000 miles to the west sits another testing site at a Presbyterian church on a West Philadelphia block filled with trees and brown brick row homes with open front porches, where cars and buses whiz by outside. One floor down in the basement, physicians, nurses, social workers, pharmacists, and dentists in training treat neighborhood residents, providing physicals and blood pressure checks, as well as the rapid-test HIV screening that Miller, a Penn School of Nursing student, performs under supervision of Penn Medicine faculty members.

They’re a world apart—except that there is precisely one minute, as Miller would come to recognize, when they’re exactly the same.

Miller is a volunteer nursing student coordinator at the United Community Clinic (UCC) in the First African Presbyterian church, a student-run preventive care clinic founded by medical students and professors that has been treating neighborhood residents for nearly 25 years. For years, partner HIV organizations, like Philadelphia Fight, camped out in the clinic to offer the testing for patients, but in late 2019, with the help of a Penn Medicine CAREs grant, UCC volunteers certified the space to be a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-approved testing site so it could be performed by Penn staff. Today, patients who walk through the door are offered free testing during their clinical visit in a private area away from the other services.

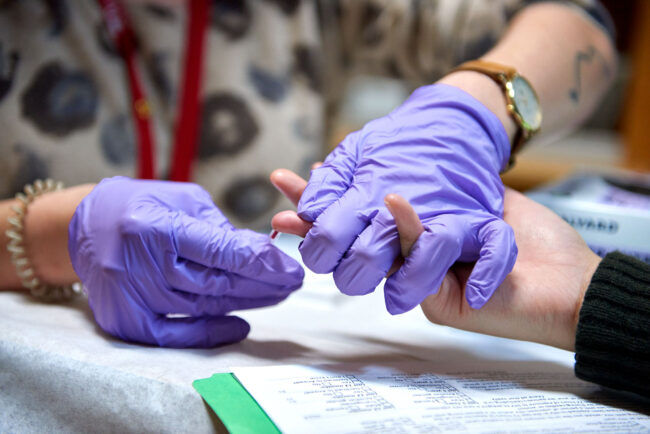

A patient’s blood is drawn and placed in a small tube filled with reagents that react to HIV antibodies an infected person would produce. In just a minute, the result is in. While patients wait for that result, though, nursing students counsel them, acting as a support system to calm nerves, answer questions, or simply be a distraction.

Even the most assured person needs that care, like the gregarious veteran who walked into the clinic one night asking for a test. They had little reason to worry, having been routinely tested every six months as part of their 15-year career in the military and no other evidence to suggest a higher risk of infection.

“But then I prick their finger, and immediately all the blood drains from their face,” Miller said. “They are quiet and do not say a word for the full minute. You could be so experienced with this, and confident in your status, but still feel a certain way.”

“Negative,” she told the patient. “The person appeared back to normal and chatty again right afterward.”

One testing session inspired a young man from West Philadelphia, thankful for the preventative information a nurse discussed with him, to pursue training to become an HIV coordinator himself to engage more with his community. The team directed him to the city’s AIDS Activities Coordinating Office under the Department of Public Health for opportunities.

Philadelphians are infected with HIV at a rate nearly five times the national average. That disparity is particularly evident in West Philadelphia communities, which have the highest incidence of new infections in the city and where more than 25 percent of adults have never been tested.

Testing remains one of the most important strategies for reducing transmissions, said Anne M. Teitelman, PhD, an associate professor in the department of Family and Community Health in the Penn School of Nursing, a nurse practitioner, and an HIV prevention researcher at Penn Medicine. It’s not only about identifying patients who need care, but also serving the community, because, as research on medication adherence has shown, once someone who tests positive is treated and maintains that treatment, they can no longer spread the virus.

Although HIV testing resources are available in hospital systems, community health centers, and free testing sites around the city, the familiar UCC site offers HIV testing resources where people in the East Parkside neighborhood of West Philadelphia feel comfortable going.

“You need different opportunities for different communities,” said Teitelman, who serves as the co-director of HIV services at UCC. “It’s not a one size fits all, and there’s a great place for everyone to go. I think having it locally in this community that is very hard hit by poverty and other types of disparities means increased access to HIV testing that’s local, free, and convenient. UCC fills those gaps in services out there.”

The clinic is made up of an interdisciplinary group of students and faculty members from across Penn schools. On any given Monday night between 6:00 p.m. and 9:00 p.m., about 20 student volunteers see 20 to 25 patients. It’s a holistic approach to care. Patients start with a social worker and then make their way through other services, from primary care to dental to pharmacy, depending on their need.

Nursing students currently lead the HIV prevention and treatment efforts—and many of them now come from a nursing HIV case study course taught by William Short, MD, MPH, an associate professor of Infectious Diseases at the Perelman School of Medicine, and infection disease specialist at Penn Presbyterian Medical Center. Patients who test positive are sent to Short’s clinic, where they receive care at no cost.

“We sit with them, and talk about what it means, about their resources,” said Miller, who received her master’s of public health and tropical medicine from Tulane University in New Orleans before coming to Penn. “It’s an opportunity for them to talk with a team who would work with them throughout the course of treating this illness and come up with a plan that works best for them.”

Twice during a patient’s visit at UCC, which can last anywhere from two to three hours, they’re asked if they want to be tested. The number of yeses continues to grow. When the testing first started in late October 2019, about one person every week would be tested. By December, it jumped to three people a week.

Before the test, nursing students take time to speak with patients about the disease, the risks, prevention, and those treatment services that would be available to them. Next, the patient puts out their finger for the prick, and the nursing students spend the next minute working to reduce the stress or worry in the room.

“Everyone copes with that feeling of anxiety in very different ways,” Miller said. Some people choose to be quiet and alone with their thoughts. Others want to talk a lot to pass the time more quickly. “How are you feeling right now? Do you have any other questions?” she may ask them.

It’s about gauging the patient in the moment.

“What I learned from that experience in the village was that this is the time where you have to offer the most support and, if necessary, be the best listener you can be for people,” Miller said. “Because if you were in that situation, you might need the same thing.”

Being There for the Critical Minute in HIV Prevention and Care

Being There for the Critical Minute in HIV Prevention and Care