With heroism, comes risks.

The first responders who bravely stepped to the frontlines of the COVID-19 pandemic have not only put their health and the health of their families in harm’s way of a virus that has taken the lives of more than 500,000 Americans and sickened millions. They’ve faced an unprecedented level of stress and exposure to tragedy and trauma — less visible but equally dangerous impacts from the virus.

If left unchecked, these strains can manifest into mental health issues, substance abuse, or, in many cases, both. And for those already battling such issues, the events of the past year will only put them a higher risk of heading down an unwanted path.

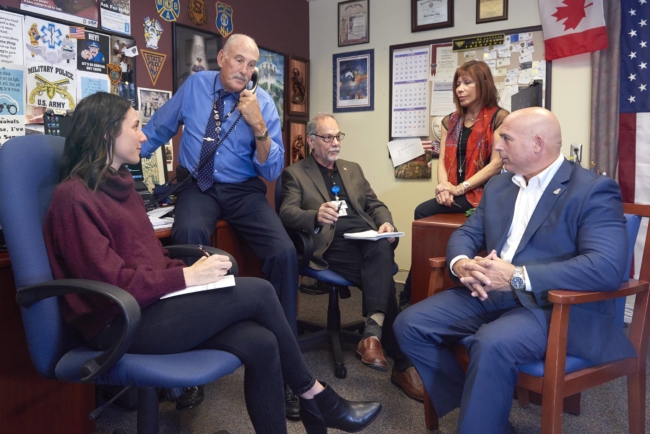

“They are not Superman, though that’s what sometimes they think,” says Michael Bizzarro, PhD, director of clinical services of the Penn Medicine Princeton House Behavioral Health First Responder Treatment Services program. “It’s really challenging for them to realize when they are affected. I often tell them: ‘Even Superman was not invincible when faced with Kryptonite.’”

“In addition to being able to help fellow first responders, I learned how to help myself,” said one detective sergeant who attended a training. “I have been struggling to find a new therapist and today I am relieved I can get one through people who understand [law enforcement officers].”

One such training served the 6,000 members of New Jersey’s Firefighters Mutual Benevolence Association and the Paterson, New Jersey Fire Department—which attends to some 30,000 calls a year.

For a high-call traffic unit like Paterson, outreach is critical, Bizzarro said. This is the time when breaking down barriers, like stigma, and bringing awareness to all the dangers of the pandemic is needed the most.

“There is a lot of internal and external pressure from the community, as well as what’s happening on the home front, because families are feeling financial stress, kids are not school, and there is not much of a break,” Dr. Bizzarro said. “There are so many factors contributing to additional stress that just weren’t there before.”

A Lifeline for the Helpers

A Lifeline for the Helpers