Nathaniel Williams is quick to say that he received good care at the now-defunct Mercy Philadelphia Hospital at 54th Street and Cedar Avenue in Cobbs Creek, the West Philadelphia neighborhood where he has lived his entire life.

But Williams, who is nearly 60 and diabetic, is just as quick to say that the care he currently receives at the PHMC Public Health Campus on Cedar — an innovative collaboration between Penn Medicine and the not-for-profit Public Health Management Corporation located in the grand old Mercy building — is the best he’s ever had.

“If everybody got the kind of care I’m getting now, everybody would be better off,” he says.

Williams is no stranger to the health care world. He worked for 10 years as an operating-room technician at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Center City Philadelphia.

Previously, if he needed medical care, he would go to Mercy’s emergency room; spend a night or two in the hospital if necessary; and be left to his own devices afterwards.

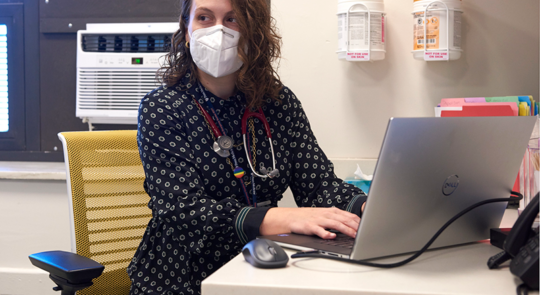

Now, however, Williams has a primary care provider: Amy Holland, MD, MA, an assistant professor of Family Medicine and Community Health at Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine who spends four days a week at the PHMC Health Center on Cedar, an outpatient clinic and Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) that launched in the northwest wing of the public health campus last November, staffed with PHMC personnel ranging from medical receptionists and medical assistants to behavioral health and social work specialists.

All the physicians at the health center are affiliated with Penn’s Department of Family Medicine and Community Health. As a result, they are able to draw on their own broad expertise as well as Penn Medicine’s extensive network of specialists and facilities to provide comprehensive, coordinated care.

“As a family medicine doctor, I provide full-spectrum medical care,” Holland says. “Any age, any complaint that walks through our doors, I want to be able to address it.”

When Williams experienced shortness of breath this past winter, he went to the emergency room at HUP-Cedar, a satellite location of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania (HUP) that is embedded in the PHMC Public Health Campus. (PHMC owns the building, while Penn Medicine leases space for HUP-Cedar and contracts to provide staff and services at the PHMC Health Center.)

After Penn Medicine physicians treated Williams for a blood clot in his right ventricle, HUP-Cedar staff immediately scheduled him for a follow-up appointment with Holland at the health center upstairs. Since then Holland has managed all aspects of his care: She referred Williams to a HUP-Cedar cardiologist for his heart issues; rushed him back to the emergency department when he called her describing the symptoms of a stroke; and even sent him to the Scheie Eye Institute at Penn Presbyterian Medical Center to see if his diabetes had damaged his eyes. It had, and he is now receiving treatment for that, as well.

This continuity of care is precisely what Penn Medicine and PHMC had in mind when they joined forces.

Working as part of a coalition that includes Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the Independence Blue Cross Foundation, the organizations are collectively building a new kind of community-centered resource hub that isn’t just about treating illness, but about promoting and sustaining public health: a hub that is accessible to all regardless of age, income, or insurance status; expands access to primary and preventive care to reduce emergency-room visits and hospital stays; and addresses the historic health inequities that have for generations afflicted the people whom it serves.

“We really want to look at the health and well-being of individuals and families as a whole, not just the emergencies that people typically go to the hospital for,” says Aunya Grimsley, Community Engagement Director at PHMC.

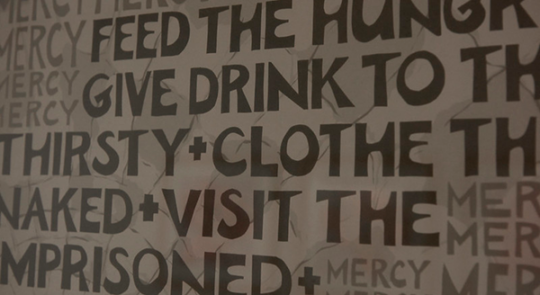

The hospital was founded as Misericordia Hospital by the Sisters of Mercy in 1918, and later became Mercy Philadelphia, part of Trinity Health Mid-Atlantic. In 2020, Trinity announced it planned to close the site.

A Crisis Averted

When Trinity Health Mid-Atlantic, Mercy Philadelphia Hospital’s parent company, announced in 2020 that it planned to shutter the site, many feared a repeat of the Hahnemann University Hospital closure of 2019.

Like Hahnemann in Center City, Mercy — which was founded as Misericordia Hospital by the Sisters of Mercy in 1918 — had for decades functioned as a safety-net hospital, providing essential medical services to an underserved and underinsured population disproportionately affected by everything from chronic disease to gun violence. Grimsley, who grew up in the area, is certain that many community members would simply have lost access to health care altogether had Penn Medicine, PHMC, and their coalition partners not stepped into the breach, mapping out a transition plan with Trinity Health to achieve their vision for a public health campus.

“I was raised in West Philadelphia. My grandmother, my aunt, they all still live here. This is a campus that they could access if they were in need,” Grimsley says. “It’s important to me that the quality of care here is top-notch, because it affects my family directly and I’m a product of this community.”

This is true even though HUP and Penn Presbyterian Medical Center, in University City, are only about two miles away. For many West and Southwest Philadelphia residents, even that seemingly short distance presents an insurmountable barrier: Parking fees, slow public transportation, and work and family obligations make it difficult to leave the neighborhood for anything but the direst medical emergencies.

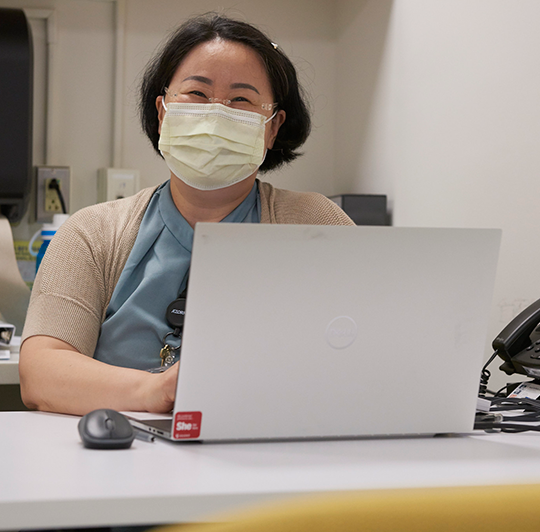

“If you look on the map, it doesn’t seem like it’s so far,” says Kristina Laguerre, MD, MPH, who practices alongside Holland at the PHMC Health Center on Cedar and also continues to see patients in University City. Yet as she points out, it can take a patient from West or Southwest Philadelphia well over an hour to reach HUP at 34th and Spruce. “That really is a burden, and it really is a barrier to them accessing care,” says Laguerre, who adds that most of her patients live within a 10-block radius of the Cedar campus.

That’s why it was important for the partner organizations to ensure local residents had access to care without interruption during the transition.

According to Sebastian Ramagnano, interim associate executive hospital director at HUP-Cedar, the Mercy emergency room transitioned seamlessly to HUP on March 25, 2021 — along with a medical ICU, two inpatient psychiatry units, a detox unit for patients with substance-use disorders, and three floors of hospital beds.

The Emergency Department had already been renovated and expanded by Trinity Health within the last few years. While operations continued, Penn Medicine stepped in and began modernizing other areas of HUP-Cedar, updating everything from clinical equipment to internet network wiring. Outpatient services, which had already been phased out at Mercy, were rebooted in the fall when the PHMC Health Center on Cedar came online as an FQHC.

Lowering Barriers to Care

Federally Qualified Health Centers receive federal grant funding to improve the health of underserved and vulnerable populations. They must provide services regardless of patients’ ability to pay, and charge for those services on a sliding fee scale — a necessary step towards making affordable primary care available to the many uninsured and underinsured residents of West and Southwest Philadelphia who for years have had to rely on the ER as their sole gateway to medical treatment.

“At the end of the day, we should be able to provide care for anyone who needs it,” Laguerre says.

In keeping with that philosophy, virtually every aspect of the campus was engineered to lower barriers to care, financial or otherwise.

The PHMC Health Center on Cedar, for instance, has a social worker who helps patients secure emergency health insurance, as she did for a patient who required brain surgery; and a referrals coordinator who makes sure that any specialists involved actually accept the insurance that a patient holds. The health center also uses the same electronic health record software as other parts of Penn Medicine, facilitating the flow of patients between primary, emergency, and specialty care.

A patient admitted to HUP-Cedar, for instance, can easily get a follow-up appointment at the health center. Ramagnano estimates that HUP-Cedar’s emergency room, which saw 37,000 patient visits in its first year of operation, currently sees approximately 100 patients per day, admitting anywhere from 7 to 20 of them for overnight observation or longer stays. The average length of stay for a HUP-Cedar inpatient is five days, but a person requiring placement in a long-term care facility may stay for weeks or even months. And more transitional services are in the works: PHMC has plans to offer medical respite programming for individuals experiencing homelessness who are not well enough to return to an unstable housing environment after they are discharged from inpatient or emergency care.

Both walk-ins and scheduled appointments are welcomed at the health center. To date, many patients have made their first appointments after visiting HUP-Cedar’s emergency room and receiving a referral for follow-up care. And as awareness of the public health campus grows, so too do the health center’s numbers: The clinic received more than 1,400 visits in its first nine months of operation, more than 300 of those in July alone.

Nathaniel Williams stopped to make an appointment for one of his adolescent sons to see his doctor, Amy Holland, MD, MS, during a recent visit to the health center.

Similarly, if a health center patient requires acute care, they can just as easily be sent downstairs to the HUP-Cedar ER, where their records will be immediately accessible to Penn Medicine’s emergency physicians. And for a specialist within the larger Penn network, like the ophthalmologist who examined Nathaniel Williams at the Scheie Eye Institute, a referral from the health center looks like any other Penn Medicine patient.

That specialty care is coordinated by the physicians at the health center, who act as medical quarterbacks for their patients.

“She knows exactly what I’m doing in real time. You just can’t beat that,” says Williams, who says he also he intends for his two adolescent sons to begin receiving care from Holland, as well.

Doing It All

Providing integrated, coordinated care is a core tenet of family medicine. So, too, is caring for all patients regardless of medical condition, gender, or age.

So far, the youngest patient treated in the health center was a six-month-old; the oldest, a nonagenarian. The range of available services is equally broad: Suboxone treatment for patients grappling with opioid use, prenatal care for pregnant people, gender-affirming hormone therapy for transgender adolescents and adults.

“We do it all,” Holland says. “We welcome every patient who walks through our doors, and provide the comprehensive care each patient needs.”

That approach is especially important when working with a population of patients who may have gone years without consistent care, leading to many untreated or undertreated ailments— including mental health disorders.

The last community health needs assessment conducted in the area identified mental and behavioral health as urgent needs.

Holland and Laguerre have both been struck by the sheer amount of trauma their patients have suffered. Some of that trauma stems from long-standing problems such as gun violence and systemic racism, and some of it is due to the coronavirus pandemic, which has disproportionately affected the same vulnerable populations that FQHCs are designed to serve — low-income families, people of color, and the underinsured.

“Sometimes I sit in visits and try to hold back my tears, because what they’ve been through is unreal,” says Laguerre, who hails from a Haitian immigrant family and is familiar with many of the struggles that her Black and brown patients have experienced.

The physicians in the health center are comfortable treating conditions such as anxiety, depression, and bipolar disorder. But a team approach rounds out the care: In addition to the psychiatrists at HUP-Cedar, clinic staff also includes a psychiatric nurse practitioner who helps manage patient medications, and a licensed behavioral health consultant who can provide therapy until long-term solutions can be found nearby.

And more help is on the way: The community previously had access to a Crisis Response Center, or CRC, to provide emergency care for individuals experiencing mental health or substance-use crises, but like the hospital’s outpatient services, it was shut down prior to the hospital’s closure. Now, HUP-Cedar was recently awarded approval from the city to establish a new CRC. The CRC is in the design phase and slated to open in early 2023.

A Commitment to Community

Like accessibility, the emphasis on providing community-centered care also finds expression in manifold ways across the public health campus.

Grimsley, for example, manages a Community Advisory Board, or CAB, comprised of West and Southwest Philadelphia residents and community leaders. The CAB, which includes representatives of organizations such as the Southwest Community Development Corporation and Wharton Wesley United Methodist Church, helps the campus’ coalition partners better understand the community they serve so that they can improve the services they provide.

Grimsley also connects regularly with the Cedar Auxiliary, a volunteer organization of neighborhood residents that traces its origins to 1915, when a “Ladies’ Auxiliary” was formed to support the not-yet-opened Misericordia Hospital. The Auxiliary includes many longtime community members who formerly supported Mercy through fundraising and volunteer work, and who now do the same for the PHMC campus and HUP-Cedar.

The Auxiliary and CAB also offer feedback on community engagement efforts; help spread the word about the health center; and even offer input into the design of the campus, parts of which are still undergoing renovation. Visitors to the clinic, for instance, are greeted by vibrant orange walls — a direct response to community members’ requests for bright colors and warm, welcoming spaces.

Yet the CAB and Cedar Auxiliary represent only two facets of a campus-wide commitment to community, which is in turn intimately related to the campus coalition’s mission to promote public health and health equity.

While providing high-quality emergency and inpatient services is vitally important, PHMC, Penn Medicine, and their partners ultimately aim to help community members remain healthier so they have less need for emergency room care and hospital stays, particularly for conditions that disproportionately harm Black and other marginalized populations.

That goal is advanced not only through routine primary care at the health center, but also by expanding into other aspects of preventive health. Like the health center for primary care, plans are underway to open a PHMC Dental facility, following a similar model partnership with Penn’s School of Dental Medicine as part of its commitment to continually expand its community presence; dental care will be provided by a mix of dental students and AEGD residents at a state- of-the-art, 11-chair facility. Penn Medicine is also building programs that increase the availability of preventive services such as cancer screenings. In June, for example, Penn Medicine partnered with the medical device manufacturer Siemens to park a “mammo truck” offering free mammograms outside a church on Cedar Avenue — part of an effort to improve access as well as equity for Black women, who tend to be diagnosed with breast cancer at later stages and have worse outcomes.

It is also furthered by efforts to address what public health experts call the social determinants of health: The constellation of social and economic factors (housing and food security, education and employment) that influence the health and well-being of individuals and groups.

Bolstering those factors in underserved areas like West and Southwest Philadelphia means tackling longstanding inequities not only in health care and insurance, but also in the availability of things such as job opportunities and healthy foods. The campus hosts a pop-up food pantry run by the Food and Wellness Network (FAWN) that gives away fresh food and produce in the building’s atrium every Thursday afternoon. FAWN is run by Turning Points for Children, a subsidiary of PHMC that provides care to children and families across Philadelphia. There are also workshops on financial literacy in collaboration with Franklin Mint Federal Credit Union. And the Cedar team has deployed employment and business-development initiatives, holding job fairs to recruit employees from within the community and working with the CAB to create a list of local businesses approved to hire as campus vendors.

All of these activities form part of an overarching plan to turn the campus into a hub for whatever resources are needed to improve the health and well-being of the community — for the community as a whole, and for each individual in need, like Williams.

While visiting Holland in the health center one day, Williams got into a conversation with a PHMC employee about his family, and came away with a boatload of information on educational and career opportunities for one of his sons, who is on the autism spectrum.

“For the community, the change is for the better,” Williams says. “It may be the same building, but it’s not the same hospital.”